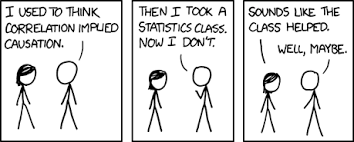

Figure from XKCD – https://xkcd.com/552/

On Twitter, Alex Trembath laments that –

Environmentalism is weird. We want a Green New Deal, but not if moderates adopt it. We want vegan meat, but not if Burger King sells it.

The issue that Alex points too is of course not new, and goes by several names – tribalism, narrative following, story telling. There are perhaps fewer topics on which opposing narratives dominate public discourse than climate change. Some narratives diverge and some run in parallel, but it is clear that an inability to construct coherent narratives is an essential and unfortunate feature of climate change mitigation and the capability of collective action. So we end up with contradictions. There are a lot of examples, but here are four that came to mind –

- Why do renewable proponents dismiss or play down bird kills from wind turbines or concentrated solar?

- How do we reconcile the idea of ‘green growth’ within a capitalist system that requires growth while acknowledging physical limits on a finite planet?

- Why are environmentalists who oppose chemicals in our environment so enamoured with battery electric vehicles and home-based lithium-ion batteries?

- In Australia, why are some of the right-wing climate sceptics interested in nuclear power (if is economic), while environmental groups and the Australian Greens are categorically opposed?

We like to think of Homo Sapiens as capable of rational thinking. Somewhat ironically, intelligence and education allows us to better rationalise thoughts and opinions that are really based on feelings and herd belonging. We are all guilty. The way that I think about the problem is that humans are instinctively essentially the same as our forebears at least from the appearance of anatomically modern humans 200,000 to 150,000 years ago, and probably longer. We collected food, hunted, and avoided getting eaten. Being part of a group vastly improved our survival. We are hard wired for social interaction and belonging. In Home Deus, Yuval Noah Harari argues that –

The basic abilities of individual humans has not changed much since the Stone Age. But the web of stories has grown from strength to strength, thereby pushing history from the Stone Age to the Silicon Age. It all began about 70,000 years ago, when the Cognitive Revolution enabled Sapiens to start talking about things that existed only in their own imagination.

In The Psychology of Silicon Valley, Katy Cook makes it even clearer –

Evolutionarily, myth-making is a hugely beneficial psychological mechanism. Narratives help us fill in the gaps of our knowledge and experience the world as more controllable and coherent. By putting our faith in a variety of cultural narratives—whether religious, political, or social—we give intelligibility and structure to our experience, which feels far more comfortable than trying (and often failing) to piece together disparate bits of information about the world. Because narratives are developed not necessarily to inform, but to ensure psychological cohesion and social cooperation, our stories often come at a price and there is often a tension between the stories we tell and the facts we encounter.

While myths may help us do many things—order our experience, set behavioral expectations, better understand the world around us—they cannot act as a barometer of truth. Many ancient and religious myths, for example, we now recognize as socially constructed to illustrate moral precepts or reflect cultural values, rather than convey facts. You may not literally believe the story of Moses’s journey to Mount Sinai, but you might still orient your life around the principles of the Ten Commandments.

Recent Comments